Houston Heights West, East and South Menu

About the District

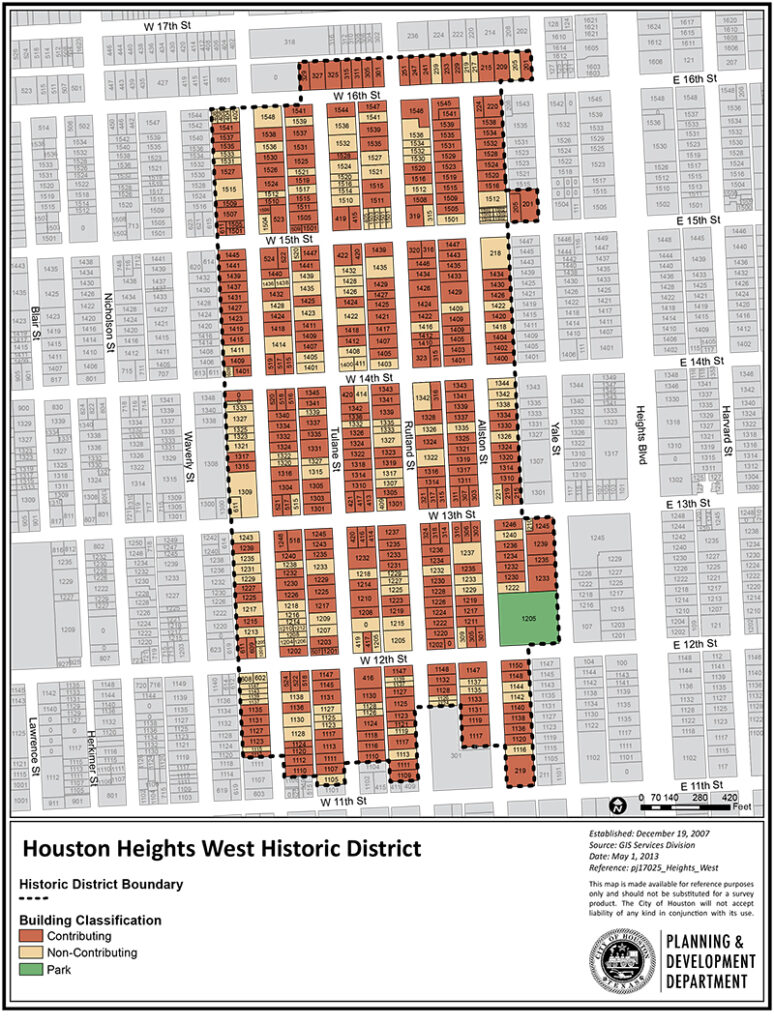

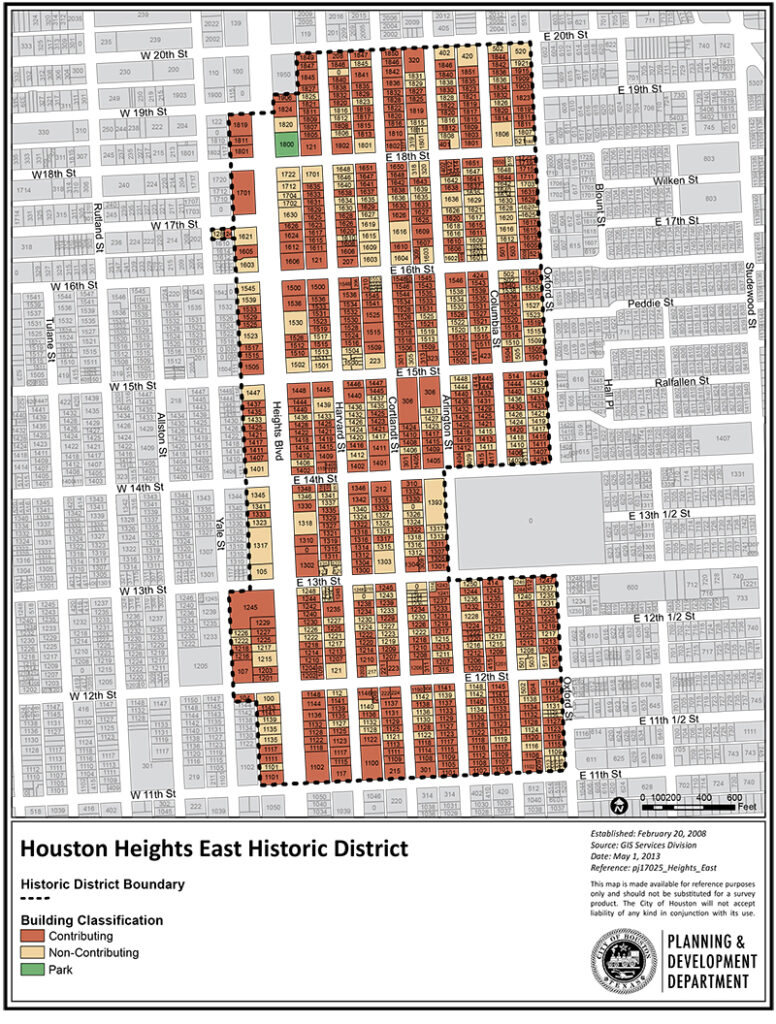

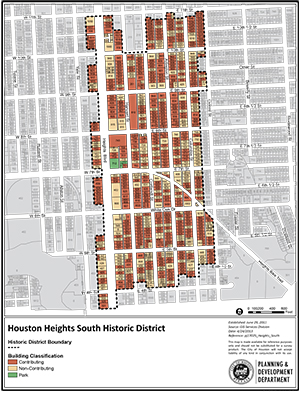

Boundaries

History and Culture

Architectural Styles

Defining Features

Setting

Heights Design Guidelines

About

Houston Heights was founded in 1891. It was Texas’ earliest planned community. Houston Heights was incorporated as its own city in 1896. It was annexed by the City of Houston in 1918. The Houston Heights includes a variety of architectural styles from the turn of the century.

The Omaha and South Texas Land Company was formed in 1887 as a subsidiary of the American Loan and Trust Company. Oscar Martin Carter, a former bank president from Nebraska, managed it. Carter hired one of his bank employees, Daniel Denton Cooley, to be the treasurer and general manager of the new company. In 1890, company representatives came to Houston to look for land and to start a new town.

The company purchased 1,756 acres of land in 1891. The land was northwest of Houston and 23 feet higher in elevation. The elevation was important to the new development’s success. Because of Houston’s low elevation near the coast, mosquitoes were plentiful and yellow fever, malaria and cholera outbreaks were common – and often fatal. As the city grew, developers tried to solve this by improved sanitation and water systems, they also looked to the area north of downtown, which at a higher elevation, seemed to have fewer mosquitos. This area became a popular location for Houston’s new suburbs.

In 1892, the Omaha and South Texas Land Company sent Cooley and other representatives to oversee the development of their land. The company built streets, sidewalks, and utility systems. They also led efforts to electrify Houston’s streetcar system and extend the streetcar lines to Houston Heights allowing people to work downtown but live in the new community.

The neighborhood was laid out on a rectangular grid with a north/south emphasis, with Heights Boulevard as the central spine. The north-south streets have names; the east-west streets are numbered. Heights Boulevard also serves as the dividing line between ‘East’ numbered streets and ‘West’ numbered streets. Some streets were named for colleges and universities, such as Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and Oxford. Other streets were named for cities in New England, where the American Loan and Trust Company was founded. Heights Boulevard features a 60-ft esplanade inspired by Commonwealth Avenue in Boston.

Lots were platted in a variety of sizes so that both wealthy and working-class people could afford to buy them. The typical residential block contains 24 residential lots, each 50-ft wide. Corner lots and lots allocated for churches, schools, or important houses on or near Heights Boulevard, were often larger in size. The residential lots were oriented so that most buildings face east or west. This orientation helped counter Houston’s hot humid summers and subtropical climate. Exceptions to this grid pattern were the areas west of Yale and north of 16th St, which had a north/south orientation. Retail was mainly located on 19th Street west of Heights Boulevard, but also developed along 11th and 20th Streets. The town plan also included industrial and commercial areas, to create a complete city where people could live, work, and shop. Those areas have undergone significant changes and, therefore, are not included in any of the Heights Historic Districts. After the land was platted, the Omaha and South Texas Land Company needed to do something so that people would buy lots in the neighborhood. It hired the Houston Land and Trust Company to build 17 elaborate homes along Heights Boulevard and Harvard Street. One of those was Cooley’s own house, at the northeast corner of 18th Street and Heights Boulevard where Marmion Park is now located. Carter also built several commercial buildings, including a hotel, on West 19th Street, near Ashland Street. The commercial area started to grow, and that attracted new residents, too.

W.G. Love served as its first mayor. He was followed in that office by John A. Milroy, David Barker, and Robert F. Isbell. J.B. Marmion was the last mayor of Houston Heights before it was annexed by the City of Houston. Two parks in the Heights are named for former mayors – Marmion Park and Milroy Park at Yale and 12th Streets, near the former fire station.

Houston Heights had its own schools, city hall, jail, fire department, and hospital. In 1918, residents of Houston Heights wanted more money for their schools. They agreed to be annexed to the City of Houston in order to access a broader tax base for school funding. As part of the annexation agreement, the Heights kept its “dry ordinance,” which banned the sale of alcoholic beverages in large portions of the neighborhood. The dry ordinance was passed in 1912, eight years before Prohibition became law across the United States. Even after the end of Prohibition in 1933, the Heights remained dry. The ordinance was upheld by the Texas Supreme Court in 1937. It wasn’t until 2016 that Houstonians voted to allow the sale of alcohol in grocery or liquor stores and in a 2017 vote, the Height’s was no longer dry

Houston Heights’ original development included deed restrictions that controlled setback, use, quality, and size of construction in the city. The deed restrictions created a consistent look and feel for Houston Heights. After it was annexed to the City of Houston in 1918, the deed restrictions were no longer enforced and properties began to change. Small houses were built in the spaces between large houses and some large homes were replaced by apartment buildings. The neighborhood declined.

In recent years, the neighborhood has been revitalized. Modern buildings are being built on vacant lots, using traditional details in order to blend in with the rest of the neighborhood. The Houston Heights Association was organized in 1973 to promote revitalization. That organization currently has about 1,000 members and manages new deed restrictions adopted in various sections of the neighborhood. For more information, contact the Houston Heights Association.