Avondale East – Menu

About

Avondale is a subdivision in the Montrose area of Houston, just a few miles west of downtown. It was designed to compete with other upscale neighborhoods, such as Courtland Place, Montrose, and Westmoreland. Today, the original Avondale neighborhood includes two historic districts: Avondale East and Avondale West, which were developed in the early twentieth century. Avondale homes were built in the Tudor Revival, Prairie, American Four Square, and Craftsman styles. Some of the neighborhood’s red concrete sidewalks and curbs, carriage houses, and hitching posts are still present today.

In 1906, Joseph F. Meyer, Jr., was a Houston businessman who owned a 31-acre pasture in the country outside Houston. Meyer sold the land to the Greater Houston Improvement Company in 1907 for $105,000. Mr. Meyer’s timing was terrific. Before 1900, most business and professional people lived south of downtown, along Main Street. By 1908, upscale neighborhoods were beginning to expand beyond the Main Street corridor. The South End line of the Houston Electric Street Railway was extended so people could travel to work by streetcar. Avondale would become one of these upscale “Streetcar Subdivisions.”

The company platted the land into 129 lots along three main streets. The streets were paved with oyster shells and the curbs and sidewalks were concrete. The company hired Teas Nursery to plant 500 trees. Every lot had gas, water, and sewer connections. Alleys were cut through the middle of each block, at the back of the lots and all of the utility poles were in the alleys. Deliveries and trash collection also used the alleys. All of this was in an effort to keep the neighborhood more attractive.

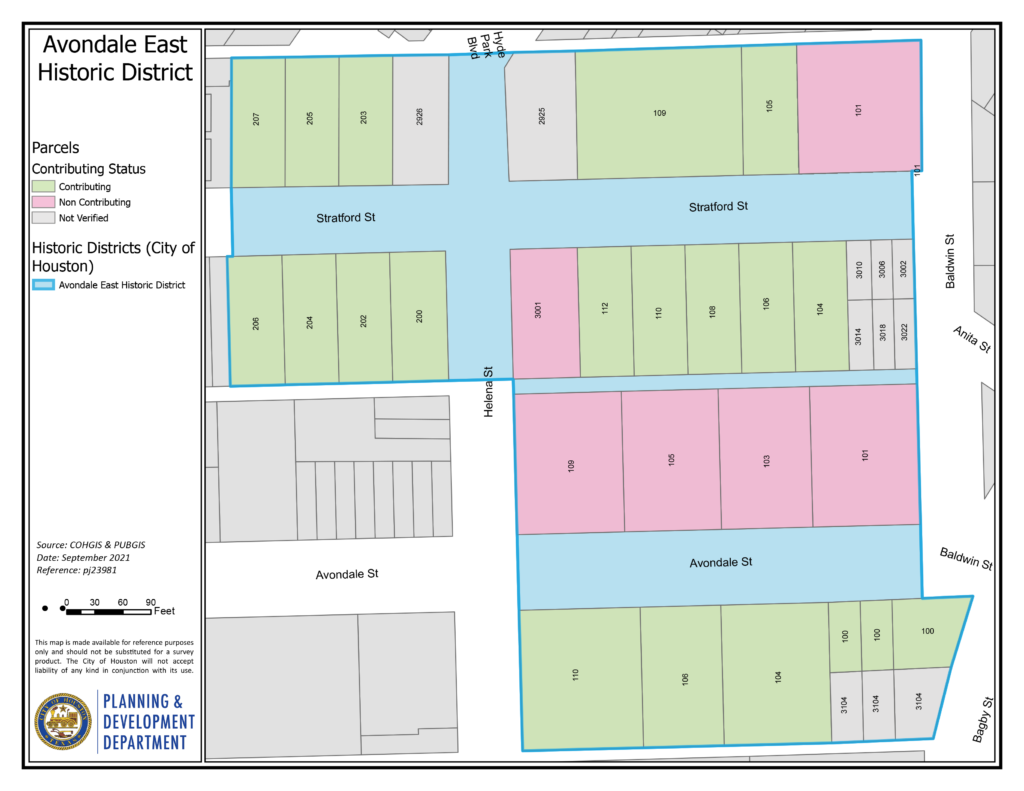

When it came time to name the subdivision, the company held a contest. It offered a $25 prize to whoever submitted the winning name. Nine contestants suggested “Avondale”, based on William Shakespeare’s hometown in England: Stratford-upon-Avon. The prize money was increased to $27 so it could be divided evenly, with each winner receiving $3. The three main streets were named in keeping with the Shakespeare theme: Avondale, Stratford, and Hathaway (now Westheimer). (Shakespeare’s wife was Anne Hathaway.) Cross streets included Baldwin, Helena, Mason, and Taft.

From the beginning, the neighborhood was designed to be upscale and exclusive. Deed restrictions ensured that it would develop as planned. No apartments, hotels, lodging houses, duplexes, or businesses of any sort were allowed. Some deed restrictions were specific to each street, allowing the company to market the neighborhood to three different income levels. The most affordable street was Hathaway. Lots on Hathaway Street were 5000–6000 square feet in size and houses had to be set back at least 25 feet from the street and cost at least $3,000. Avondale, the most expensive street, had 10,000 square foot lots, with a minimum 35-foot setback. Houses on Avondale Street were required to cost at least $5,000. On Stratford Street, houses had to cost at least $3,750. Some wealthy homeowners bought multiple lots and built large mansions.

As Avondale developed, automobiles were starting to become popular. Many Avondale residents could afford automobiles, even as commercial deliveries still relied on wagons drawn by horses or mules. Most properties in Avondale had hitching posts at the curb and a carriage house behind the main house. The carriage houses were usually two stories tall and were designed in the same style as the main house. They had space for two cars on the ground floor with a small apartment (servants’ quarters) above that. The carriage houses were usually designed in the same style as the main house.

The neighborhood developed quickly. In 1912, Avondale was expanded westward past Taft Street for four blocks. The new north-south cross streets were named Whitney, Hopkins, Stanford, and Crocker. The lots on Avondale Avenue were large, as in the original neighborhood, with a rear alley. The lots on the cross streets were the standard city residential-lot size of 5000 square feet. No alleys were built in those blocks.

The expiration of the neighborhood’s deed restrictions in 1930 had both positive and negative consequences. On the positive side, non-white people were no longer prohibited from owning property in the neighborhood. On the other hand, businesses started opening in some of the houses.

Avondale continued to change after World War II. Many of the old families moved away from Avondale. Many U.S. cities did not have enough housing for returning servicemen and their families. As old families moved away from Avondale, many of their large houses were torn down to make way for apartment buildings, which helped solve the housing crisis. Businesses took over Hathaway Street, which had been renamed Westheimer Road.

As the neighborhood enters the twenty-first century, the renewed interest of living close to downtown has helped Avondale once again become an upscale residential community.